Hi Friendos,

Today I want to talk about investment fees because you will be wealthier if you stop financial firms from skimming your cream. I think this is so important that your written financial plan should include a statement like the following:

“Stephanie will strive to minimize the effects of expenses on her investment returns.”

I want to get into how mutual funds actually levy these fees, since you never get a receipt or itemized report for them. But first, another a tax season plug for the IRS’ Direct File program, which I wrote about in January.

Direct File lets people in 25 states file their taxes directly with the IRS for free. Last year, after filing through Direct File, more than 15,000 taxpayers completed an optional survey and 90% said their experience was “Excellent” or “Above Average.” More than half said their filing experience was “much easier” than the prior year. Here is what selected taxpayers said about Direct File after using it:

“Greatly appreciate the opportunity to file directly with the IRS rather than a third-party provider. The system was easy to use and understand.”

“I design many forms for my job and conduct accessibility audits of them, and this entire experience just made my heart leap for joy. A few years ago, I was brought nearly to tears the first time I filed my taxes with paper forms. Since then, I’ve studied a range of best practices and standards for easily usable and accessible online form design, and this Direct File system nailed every single one of them. I am so beyond impressed, and I sincerely hope this program continues and expands in the future.”

“Todo el proceso es de lo mejor, preciso y eficiente.” (The entire process is top notch, precise and efficient.)

People love Direct File! If you are eligible, I think you should try it out.

Now, onto investment fees. Recently I’ve been helping a family member with their investments and observed they held many high-fee mutual funds in their accounts. I shared this observation and explained that these mutual fund fees, called “expense ratios,” do not appear as a line item on your account statements.

A lot of people start learning about investing and hear, over and over, you have to control fees. Don’t buy funds that charge a lot of fees. So the diligent learner logs on to their self-directed brokerage account and starts looking through their investment statements to see what kind of fees they are paying. But there is nothing on the statement called “fees” and they’ve looked everywhere! When they look at their cell phone or utility bill, there are like, 11 different line items for various fees, so why can’t they find the fees here? The answer is that these mutual fund (and ETF) fees are hidden inside of the value of the fund itself.

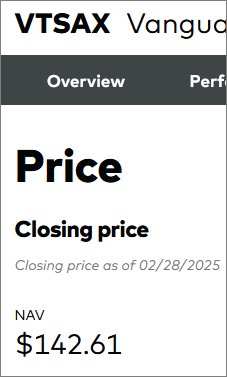

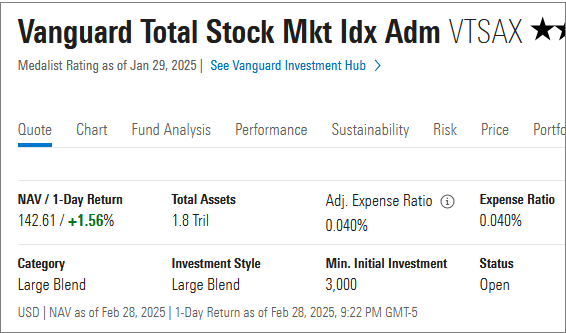

When you buy a share of a mutual fund, you pay a stated price per share of that fund. This price is also known as “net asset value” or “NAV” for short. Example: on 2/28/2024, Vanguard’s Total Stock Market index fund (ticker: VTSAX) had a price per share, aka “NAV,” aka “closing price,” of $142.61.

Vanguard.com uses all these terms on its website:

Morningstar.com refers to NAV (net asset value):

Google Finance just displays the price per share without explicitly labeling it:

And Yahoo Finance describes it as the price at close:

Is it confusing that people in the industry refer to one number in multiple ways? Yes! But now you know. So… what is a mutual fund’s “asset value” “net” of, exactly? Fees! It is net of fees!

Every day the mutual fund totes up the value of all its assets, subtracts off (“nets out”) the value of its liabilities, and divides by its number of shares outstanding to arrive at net asset value, aka, its price per share. That is the price you pay when you buy shares of the mutual fund or receive when you sell shares.

Mutual fund liabilities include accrued expenses of services the fund pays for, like having its financial statements audited, generating reports for shareholders, and paying for the portfolio managers who buy and sell the funds’ investments.

Investors buy and sell shares mutual funds every day, which means that during a given year, if you take a particular mutual fund, some of its investors hold the fund all year long, some for a big chunk of the year, and some for only a small chunk of the year. With all these different holding periods, it is only fair to pro-rate the fund’s expenses so that each investor only has to pay expenses for the portion of the year that they actually held the mutual fund.

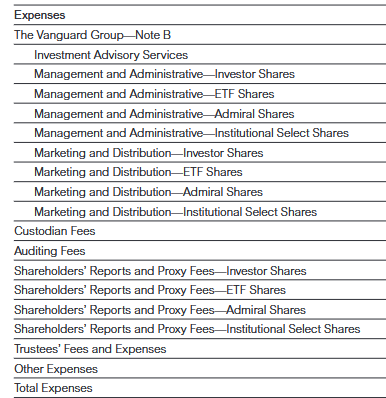

Continuing with Vanguard’s Total Stock Market Index Fund as an example, we can see the expenses it lists in its 2024 financial statements, on p. 11:

The top line references “Note B,” which says:

“In accordance with the terms of a Funds’ Service Agreement (the ‘FSA’) between Vanguard and the fund, Vanguard furnishes to the fund investment advisory, corporate management, administrative, marketing, and distribution services at Vanguard’s cost of operations (as defined by the FSA). These costs of operations are allocated to the fund based on methods and guidelines approved by the board of trustees and are generally settled twice a month.”

The mutual fund is a separate legal entity from Vanguard itself and the mutual fund hires Vanguard to provide services to it. In turn, Vanguard hires employees like portfolio managers and pays their salaries out of money it receives from mutual funds.

As the Note B explains, the mutual fund pays Vanguard (in cash) about every two weeks for these services (costs are “settled twice a month”). Although the mutual fund pays this bill twice a month, every day it becomes liable for one day’s worth of service costs. Imagine that the fund has just made a payment to Vanguard. It owes Vanguard nothing. One day later, Vanguard has provided a day’s worth of services to the mutual fund and the mutual fund is now on the hook to pay for those services. The mutual fund has a liability that will be reflected in that day’s net asset value – the per share price of the mutual fund.

This daily bookkeeping is the process by which investors pay fees for fund management. The value of your mutual fund shares always reflects your payment of fees – fund expenses – because the fees are incorporated into the per share price of the mutual fund every day. These expenses of the mutual fund are calculated as a percentage of the funds’ assets, or put differently, as a ratio. This is why mutual fund fees are described as an “expense ratio.” (Check out the Morningstar.com screen shot above – you see the Vanguard Total Stock Market Index Fund has a rock-bottom expense ratio of 0.04% – only four hundredths of one percent). And because these fees are part of the mutual fund’s own bookkeeping, they never appear on your investment account statements directly, but instead are “baked in” to your investment returns.

If your mutual fund has higher fees, it will have more dollars of expenses that get subtracted out of the value of the fund. If your fund has lower fees, you get to keep more of the investment returns. If you put your money in funds with smaller expense ratios (lower fees), your investment returns will be greater for it.

-Stephanie

One reply on “The Boring Newsletter, 3/2/2025”

[…] just goes to show that sometimes, 1% is not very much. In other settings (investment fund fees), 1% is really a lot. Sometimes (mortgages), it is absolutely enormous! You get perspective by […]

LikeLike