Hi Friendos,

While my city is trying to dry out this weekend, it feels like the perfect time to wade into tax brackets. We talked about these a bit during Summer School, but today I want to go a bit deeper.

If you have any control over when you receive your income, understanding tax brackets could help you make some moves to lower your total tax bill. It could be that you are self-employed and can decide/influence when you are paid, or maybe your family member is giving you a cash gift and you could make a request around the timing. Maybe your income will vary across a few different years because you went back to school / took an unpaid break / just life stuff – perhaps you could make some optimizing moves with the income you will receive and/or your investment accounts.

Understanding tax brackets and tax rates helps you understand other things in your financial life too, like the amount of tax benefit you would get from an HSA or FSA (I’ll write more about this before health insurance open enrollment later this fall), and how to think about different investment returns (you can only spend the after-tax amounts). It’s boring to learn about, but it can be worth a lot of $ so I think it’s good to do it anyway. It doesn’t take long.

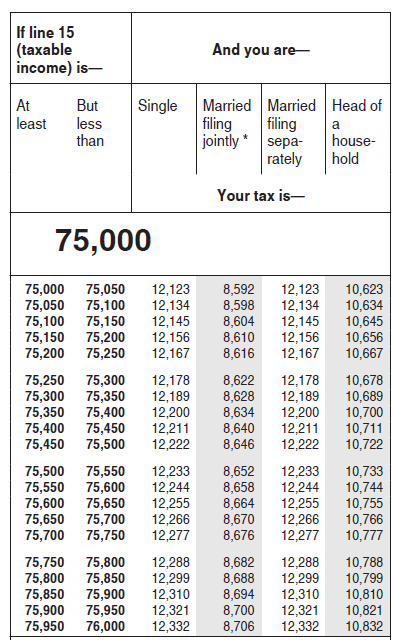

If you go to the “tax table” part of the IRS’ instructions for last year’s Form 1040, here’s a sample of what you see:

It’s a black box: you look up your taxable income in the table, read across to the column with your filing status, and it shows you the amount of tax you owe for the year. It doesn’t explain the tax brackets that lie behind that number!

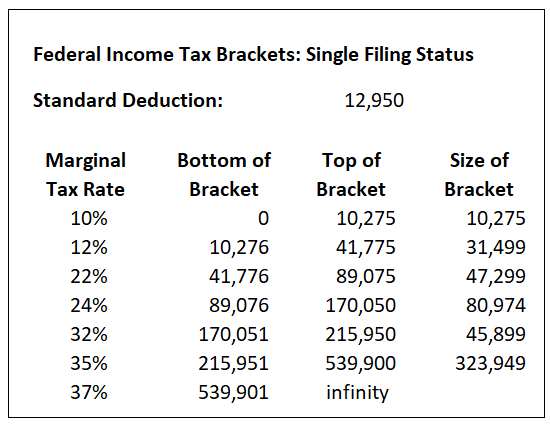

Here they are:

So to figure the amount of federal income tax you owe, you start at the top and work your way down the table to calculate the amount of tax owed on each chunk of income.

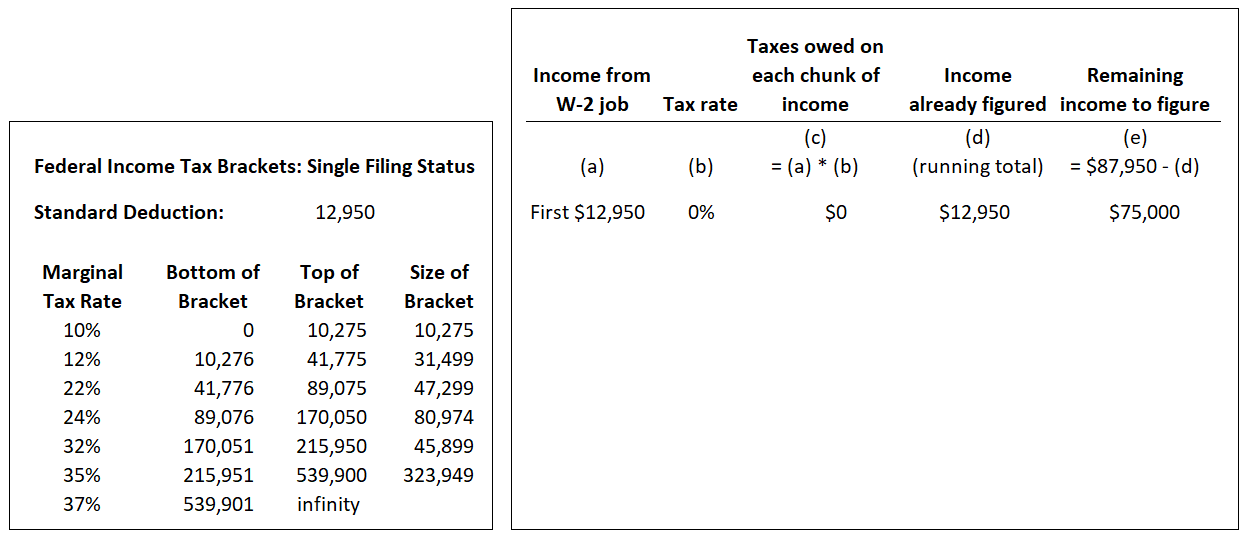

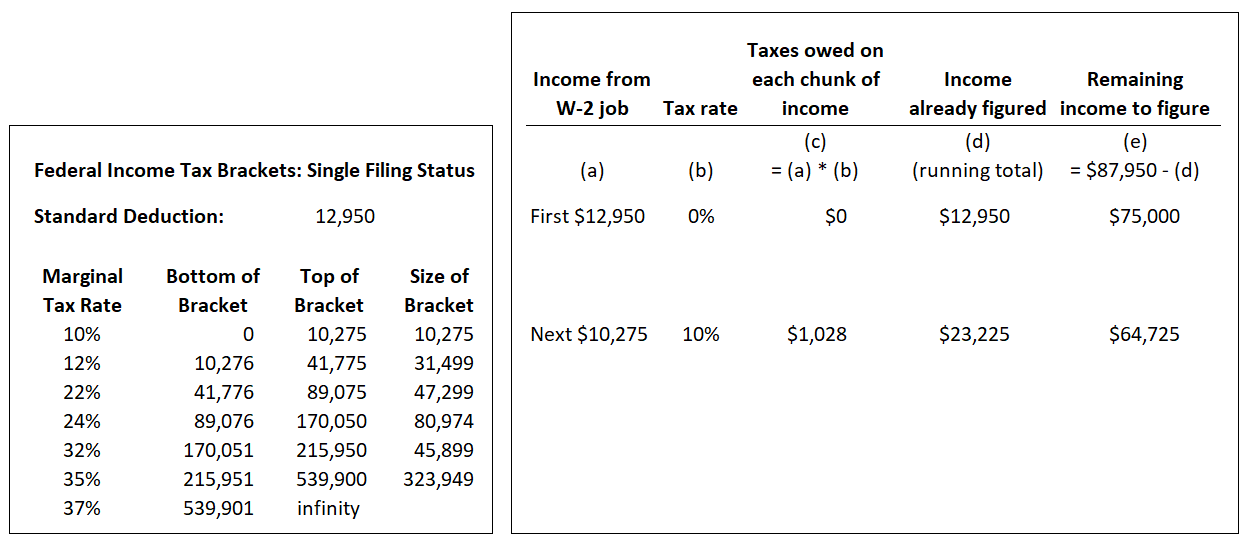

Let’s say we have a friend who files single and they have a W-2 job where they earned $87,950 last year—their boss just couldn’t go the distance for that last $50…

Like most people, they claim the standard deduction so they owe no taxes on $12,950 of their income. Another way to say that is: $12,950 of their income is sheltered from taxes. Or, you could think of as: there is a 0% tax bracket on the first $12,950 of their income. That leaves us with $75,000 of remaining income to consider (=$87,950 income minus this $12,950 chunk).

Then we move to the next bracket: the 10% tax bracket. This bracket relates to the next $10,275 of income, so our remaining $75k covers this entirely and then some. Our friend will owe 10% on the full bracket, so that’s $1,027.50 (=10% * $10,275). Now we’ve considered $23,225 of income (=$12,950 + 10,275) and so far they owe tax of $1,028.

We still need to figure things for the remaining $64,725 of their income. We can do the next two brackets in one go:

They have to pay 12% on $31,449 of their income ($3,780) and the on the last $33,226 of income, they are in the 22% bracket, and have to pay $7,310 on that. Total “federal income taxes” are $12,117. [1]

If you take $12,117 and divide it by the $87,950 of W-2 income, you get their “effective tax rate” of 13.8%. This person’s “marginal tax rate” is 22% (the tax rate on their last $ of income) but the average amount they pay on all their income is only 13.8% (because it’s a weighted average of all the brackets their income falls into).

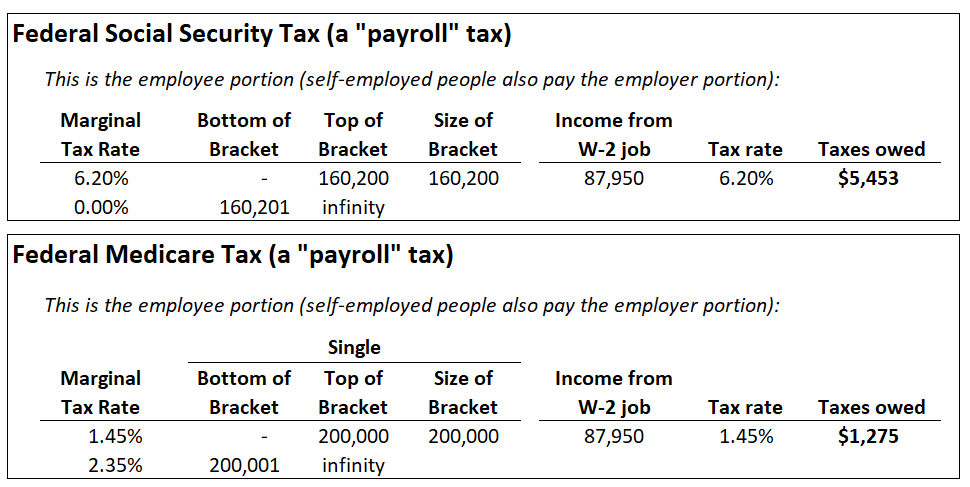

But wait there’s more! There are also brackets for Social Security taxes and Medicare taxes, and this part is not really shown on Form 1040:

In addition to the $12,117 of tax we label “federal income tax,” this person also has to pay Social Security and Medicare taxes that total $6,728. Grand total: $18,845 (21.4% of their W-2 income).

Note that the Social Security tax bracket is regressive, meaning that as your income goes up, you pay a smaller % of it in taxes. In 2022, you owed no Social Security tax on income above $160,200. The tax burden on high earners does not look quite so burdensome when you do a more comprehensive analysis.

-Stephanie

[1] If you are a more diligent reader than I would be, you might be wondering why our calculated tax amount of $12,117 does not appear in the snapshot of the tax tables from the Form 1040 instructions, even though our example friend has $75,000 of taxable income (after accounting for the standard deduction). The tax table shows $12,123 in tax, not $12,117, because the tax amount is calculated on the midpoint of the stated income range ($75,025), resulting in a few bucks more tax owed. Call it rounding.

7 replies on “The Boring Newsletter, 9/30/2023 ⛈️”

[…] Say you are single and have a salary of $75k. You take the standard deduction (using 2022 #’s here – it was $12,950) so only $62,050 of your income is subject to federal income tax (=$75k – $12.95k). You are in the 22% marginal tax bracket, as you can see in this table we looked at a few weeks back: […]

LikeLike

[…] payroll deduction, you also avoid 7.65% in payroll taxes (check out the payroll tax bracket tables here). Continuing our example from above, you would save an additional $295 off your payroll taxes […]

LikeLike

[…] find the system is regressive (distributing from lower income people to higher income people). Social Security taxes are also regressive. We could collectively decide to change […]

LikeLike

[…] might sound like a high % considering the levels of the federal income tax brackets, but freelancers also have to pay Social Security and Medicare tax (payroll […]

LikeLike

[…] life the same. This is a decision at the margin so we should use the rate of this fellow’s top marginal tax bracket. I agree with Michael Kitces that “marginal tax rates should be used to compare [financial […]

LikeLike

[…] lower rates of lower tax brackets (I walked through the math of tax brackets, step-by-step, in a prior newsletter). Now, the tax nerds among you might be sharp shooting me to point out strange edge case examples […]

LikeLike

[…] tax rate should be ~7.5% for the year. (I explain the calculation for effective tax rate in this earlier newsletter.) So you also should have sent in ~$1,500 for federal income taxes (=$20k * […]

LikeLike