Hi Friendos,

Last week I wrote about how FSAs and HSAs save you money (lowering your taxes), and I promised to talk this week about how much they can save you, so you can decide if putting your $ in one is worth it to you. This week is a deep dive on FSAs. Next week we can get into HSAs. Then we can put it all together with an analysis to choose among different insurance options (with or without an FSA or HSA). The administrative burden of understanding and using these accounts is real, so you’ll want to know if it’s worth the bother.

For FSAs, the financial benefit per year could be anywhere from $0 to about $1,400ish. Where you fall in that range depends on your tax and medical expense situation. Let’s cover some FSA basics and then go through an example calculation.

How FSAs work

Medical flexible spending accounts let you put money into a special account via payroll deductions—up to $3,050 for 2023—and then spend out of that account on qualified medical expenses. Medical FSAs are not for self-employed people, just employees. There is also a type of flexible spending account for child care expenses—those are a totally separate thing.

What is a “qualified medical expense”? The IRS has a publication on this.

- Yes: Abortion, Acupuncture, Alcohol/drug addiction treatment, Breast pumps, Deductibles, Chiropractor, Contact Lenses, Copayments, Guide dog, Hearing aids, PPE (like masks), Pregnancy tests, Prescription medication, Therapy, Vasectomy, Wheelchair. And more.

- No: Insurance premiums you pay for employer-provided health insurance. Child care to facilitate medical treatment. Medical marijuana. Diaper service. Funerals. And more.

What is considered qualified is sometimes updated, so before the pandemic, the IRS publication said nothing about PPE, but now it does. If you’re not sure, you can check the FSA section of websites where medical items are sold (e.g., Walgreens.com, FSAstore.com), see if your item is listed, and then make your purchase wherever you prefer.

Some store receipts will identify qualifying items. And sometimes the shelf labels in a store will also indicate FSA-eligible.

When you contribute to an FSA, your full contribution amount for the year is available for use on the first day of the plan year (usually Jan 1), even though it takes all year for that total to come out of your paychecks. If you leave your job and the FSA balance is negative, your employer eats the loss.

To spend the money in your FSA account, there are two methods I know of. First is to use a payment card associated with the account, it works like a debit card. Your plan administrator would send you this card in the mail. The other way is to pay out of pocket and then submit your receipt for reimbursement. When I need to do this, I usually submit right away for larger amounts (because I don’t want to wait for my money), but wait to do a few receipts at the same time for smaller amounts (batching for time efficiency – I have a designated spot where I keep “in-process” receipts). You should know yourself and go with an approach that will work for you – if you tend to lose track of paperwork over time, then do it right away. I do recommend saving receipts and any related paperwork until you have all your money in hand, just in case anything goes wrong and you need to re-submit.

One downside of FSAs is that money in the account is Use-It-Or-Lose-It. That means if you don’t use the money on medical expenses, you forfeit the funds. Except…employers can let you “carry over” up to a certain amount into the following year ($610 is the max carryover for 2023). Say you put $1,000 into your FSA but only have $780 of qualified expenses that year. If your employer’s plan allows it, you could carry the unspent $220 and use it for next year’s medical expenses. Extreme alternative example: you contribute $1,000, have no medical expenses that year, can only carryover $600, and forfeit $400.

What’s the $ benefit? (the tax savings)

It is the amount of taxes you would pay if you did not use an FSA (higher taxes paid) vs the amount if you did (lower taxes paid). This is equal to the amount of money you put into the FSA times your marginal tax rate, because contributions to the FSA decrease your taxable income.

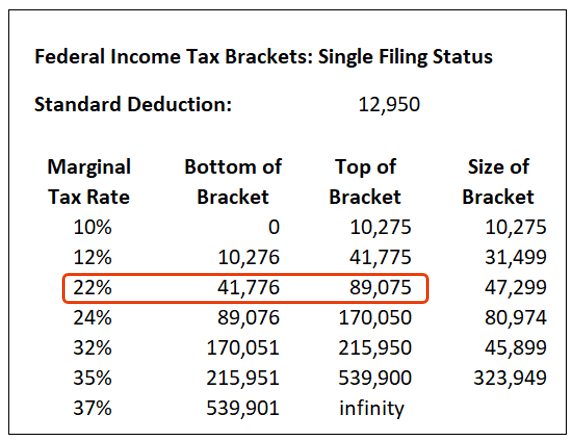

Say you are single and have a salary of $75k. You take the standard deduction (using 2022 #’s here – it was $12,950) so only $62,050 of your income is subject to federal income tax (=$75k – $12.95k). You are in the 22% marginal tax bracket, as you can see in this table we looked at a few weeks back:

If you put $1,000 in an FSA, that’s $220 saved on federal taxes (=$1,000 * 22%) because the contribution lowers your taxable income by $1,000.

The same math applies for your state (and local) income taxes, where your marginal tax rate might be 0% if your state has no income taxes up to something like 10% if you live in a higher tax state and have higher income. For this example, let’s say you have a 4% marginal tax rate on your state income taxes. If you put in $1,000, you save $40 on your state income taxes. Your total marginal income tax rate is 26% (=22% federal + 4% state) and your total tax savings is $260 (=$220 + $40).

That’s our answer: Every $ you put into an FSA and use on qualified medical expenses saves you 26 cents on taxes. Another way to think about it is that the federal government provides a 22% subsidy and the state government provides a 4% subsidy on your FSA medical spending.

What if you have a lower income and are therefore pay a lower marginal tax rate? Your tax benefit from using an FSA will be less. Say you have a salary of $50k and file single on your taxes. You are probably in the 12% bracket for federal income taxes. Say you are in the 3% bracket for state taxes. You would save 15 cents for every $ you put into an FSA (12% + 3%). FSAs provide a larger tax reduction to higher income people.

So that’s the tax savings from an FSA in the financial plus column. Any offsets to consider for the financial minus column? It’s the potential “losing it” from FSA money being use-it-or-lose-it. Every $ you forfeit is an offset to your tax savings.

I suggest people fund FSAs in the amount of their predictable medical expenses, and consider carryover amounts like a “margin of safety” in the happy event expenses are lower than predicted.

-Stephanie

5 replies on “The Boring Newsletter, 10/15/2023”

[…] open enrollment for medical insurance coming up, I’ve been talking about FSAs and HSAs. Last week we looked at quantifying the tax benefit of using an FSA. This week we do it for HSAs. Next week […]

LikeLike

[…] of these items are FSA-eligible, which is helpful if you overfunded your FSA account – use it, don’t lose it, and save your […]

LikeLike

[…] that much in unreimbursed qualified medical expenses in 2025 and wanted to take advantage of the FSA tax benefit. After factoring in federal, state, and local income taxes, that benefit is worth over $1,000 to […]

LikeLike

[…] written about them in the past, explaining how the tax benefit works and quantifying it in dollars (here for FSAs and here for […]

LikeLike

[…] getting a bit stuck in the mud with accounting for certain medical spending. They put money into an FSA offered at her job, which covers some of their medical expenses, they have some out of pocket […]

LikeLike