Anatomy of a 1040, Class 6

Hi Friendos,

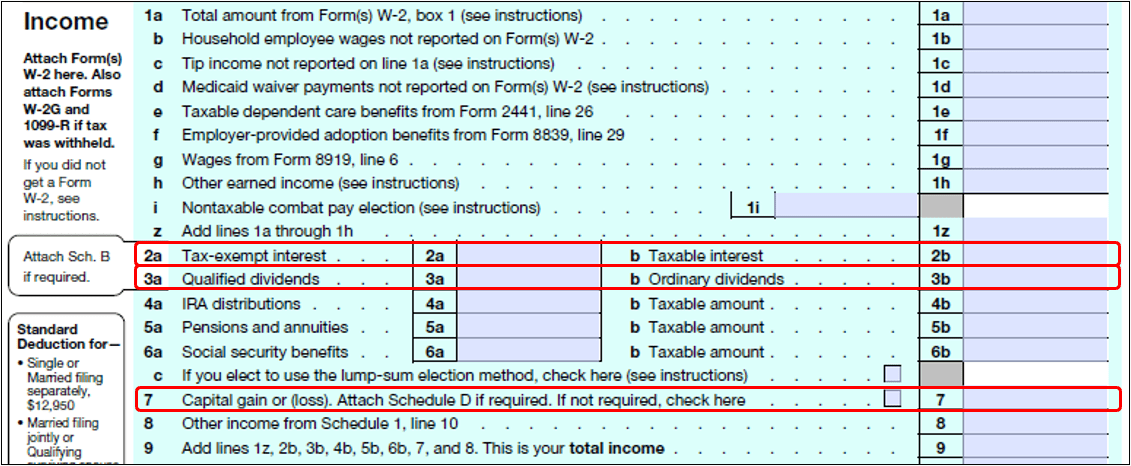

Welcome to week 6 of our summer school course on the 1040. Last week we talked about interest income; this week we’ll discuss the two other members of the investment income trifecta: dividends and capital gains.

If you have a regular brokerage account (an investment account that is not tax-advantaged, like an IRA or a 401k), you have surely received one or more Form 1099’s and had some type of investment income to report on these lines.

Form 1040 has multiple line items for these different kinds of investment income because they can be taxed differently. Before I explain how each type is taxed, let me give some overall context.

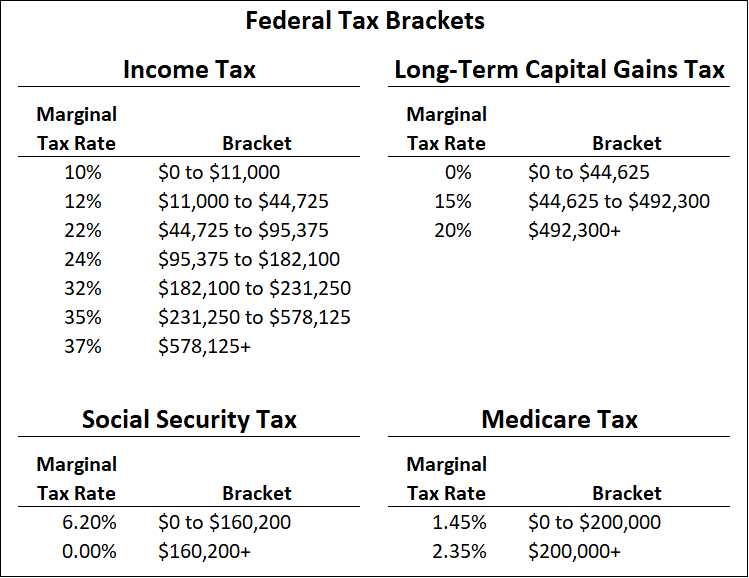

U.S. personal income taxes have 4 primary tax brackets that can come into play for federal income taxes, social security taxes, Medicare taxes, and long-term capital gains taxes. Here is what the 2023 brackets look like for a person filing “single” (for self-employed people out there, note that I am showing the “employee” portion of social security and Medicare taxes here):

The way “marginal” brackets work is that you pay the marginal tax rate for your income falling into that bracket and then pay the next rate only for income that falls in the next bracket. For example, if a single person has taxable income of $40k, they will pay a 10% tax rate on their first $11k of income and 12% on the remaining $29k. They don’t pay 12% on all $40k, only on the “marginal” portion of income that falls into that 12% bracket.

You can see in the tables above, that our $40k single filer falls into the 0% bracket for long-term capital gains. That is a more favorable tax rate than their 12% federal income tax bracket! Same goes for any other level of income.

So what’s the tax treatment for capital gains and dividends? Here is a summary:

- Short-term capital gains, nonqualified dividends: taxed under the federal income tax brackets.

- Long-term capital gains, qualified dividends: taxed under the long-term capital gains tax brackets.

What are short-term and long-term capital gains? Capital gains happen when you sell an asset (such as a house, a share of stock, or a share of a mutual fund) for a higher price than what you paid for it.

“Short-term” is if you held the asset for less than a year, “long-term” for more than a year.

What are qualified and nonqualified dividends? A company pays dividends to its shareholders when it wants to distribute some of its cash (e.g., the company has profits but does not need to retain all of them for future corporate use). Mutual funds also distribute investment gains to their shareholders as dividends.

Dividends can be “qualified” or “nonqualified.” To be qualified a dividend must be (1) from U.S. corporations or foreign corporations that trade on major U.S. stock exchanges, and (2) from investments held for a few months before the dividend was paid.

When you get a Form 1099-DIV from your brokerage firm, it lists your qualified dividends for the year (box 1b on a 1099-DIV). It also lists your “ordinary” dividends for the year (box 1a) which is the sum of qualified and nonqualified (but the amount of nonqualified is not shown separately…confusing). Form 1099-B lists your capital gains from brokerage transactions.

There is an awful lot of tax avoidance work that goes into having income treated as long-term capital gains rather than “ordinary” income subject to higher tax rates. The “carried interest loophole” is an example of this: it allows money managers (primarily in private equity and venture capital) to avoid higher income tax rates on nearly all the income from their labor. I do know of one wealthy person who intentionally structured things so they would pay more in taxes, that is Haraldur Thorleifsson, an Icelandic entrepreneur who sold his company to Twitter in 2021 and chose to receive his payout as wages (subject to higher taxes in Iceland) rather than a lump sum payout.

See you next week!

-Stephanie

2 replies on “The Boring Newsletter, 7/23/2023”

[…] it feels like the perfect time to wade into tax brackets. We talked about these a bit during Summer School, but today I want to go a bit […]

LikeLike

[…] refresher on investment income and how interest income and capital gains are taxed, you can revisit lesson 6 from our Summer School series on Form 1040. In that article, we looked at federal tax brackets, […]

LikeLike